Recently, I read an interesting article in The New York Times that provides the diagnostic criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), about the rise in diagnoses, and whether there was a one-size-fits-all understanding of the “disorder”.

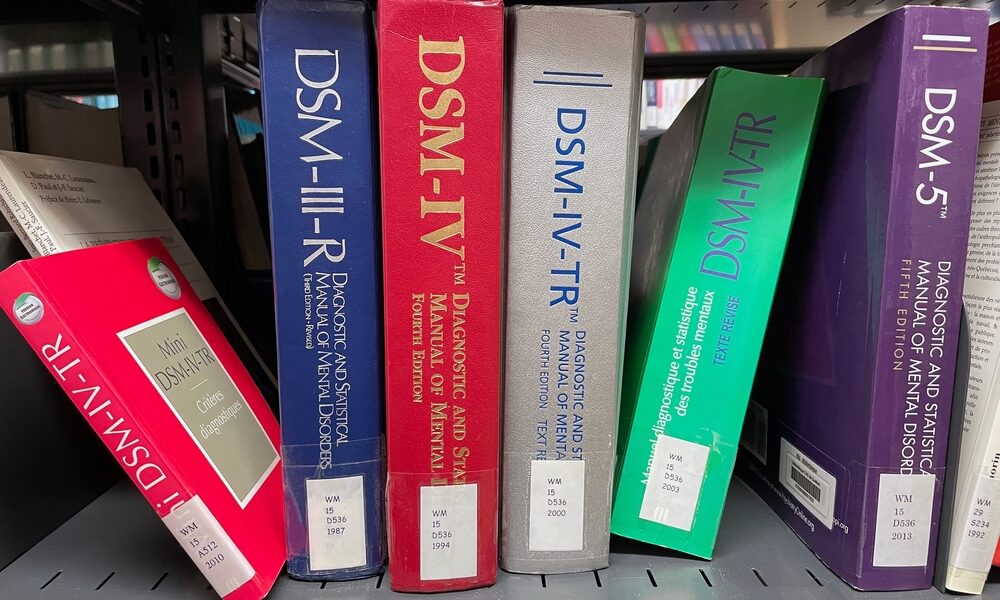

One of the conclusions of the article was that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM 5), checklist was an extremely blunt tool for determining whether an individual may be diagnosed with ADHD, despite DSM 5 being recognized as the “gold standard”.

The checklist consists of 18 symptoms, divided into two groups. Adults need to exhibit five of the symptoms in either group in the last six months to be considered at high risk of “suffering from the disorder” and should be referred for further investigation.

This means that three people could have entirely different symptoms and still be classified as high risk for having the disorder.

The article discussed several studies that found no difference in academic achievement between those who had been given medication to alleviate ADHD symptoms and those who had not.

Also, the article proposed that ADHD appears to be contextual. The inability to focus and become easily distracted depends on what the person is doing. From personal knowledge of a relative who was severely affected by ADHD, he was unable to focus on an activity for more than a couple of minutes and was constantly fidgeting, which meant that he could not hold down a job or enjoy a long-term relationship and was endlessly missing appointments, etc. But he could spend hours drawing the most detailed cartoons or playing a guitar without being diverted, no matter what was happening around him.

This appears to be saying that ADHD is not a single disorder, but many grouped under one category. Yet it manifests in different ways, depending on the person and circumstances.

DSM 5 also has a list of diagnostic criteria for a gambling disorder. Of the 10 criteria listed, a person must have experienced four in the past year in order to be at “high risk” of having a gambling disorder. Clearly then, it is possible that two people could have experienced different criteria, but still be diagnosed with the same disorder.

Similarly to what the article pointed out, I tend to think a whole spectrum of people suffer from the disorder. At one end are addicts, completely out of control. These unfortunate people cannot simply stop gambling no more than a heroin addict can just stop taking heroin.

At the other end of the spectrum (or possibly, just beyond the other end) are those that have got into “trouble” through gambling. They have gambled, lost, gambled some more, and won their losses back. The next time they gamble, the same thing happens and this goes on until they do not win their losses back. By not understanding what gambling is, that a stream of losses is not always followed by a stream of wins, they have gambled away more than they can afford. This is not necessarily someone with a gambling disorder, but they would meet the DSM 5 diagnosis.

The rest of the “disordered gamblers” sit somewhere in between.

Gambling regulators are trying to reduce gambling harms, either because it is a statutory requirement or because they believe it is the right thing to do.

I do not think anyone in the regulated sector does not believe that reducing gambling harms is a laudable aim. However, it is far from clear whether the actions taken and regulations imposed are having the intended consequences.

Regulators are taking a one-size-fits-all approach, but are disordered gamblers a unified group? Possibly yes and possibly no. Just because more problem gamblers play on online sites does not mean that online gambling is the cause.

An extreme analogy: Alcoholics tend to drink spirits (drinks with a high alcohol content), because they get the buzz more quickly. When spirits are not available, they drink wine and high-alcohol beers.

Reducing spin speeds, maximum stakes, etc. probably does very little; the disordered gambler finds the next best thing.

We live in a topsy-turvy world where the most voluble are the ones that are listened to. Gone are fact and evidence and facts appear to be what anyone wants them to be.

Gambling regulators are listening to those with lived experience and public-health experts. In the UK, the latter are far from unbiased. Those with lived experience should be listened to, but undoubtedly, they will argue against any form of gambling in the strongest possible way.

In Great Britain, the opportunity was missed when the 2005 Act was enacted. There should have been a thorough baseline study against which future regulations and their outcomes could have been tested.

Unfortunately, this was not done. Regulations are promulgated, sometimes after consultation, with the stated aim of reducing gambling harm. But so many are imposed that it is impossible to see what the impact on gambling harms of any individual regulation might be.

The scientific method is fairly straightforward: Form a hypothesis, make a prediction based on that hypothesis, design an experiment to test the prediction, analyse the data, and form a conclusion.

Where gambling regulation is concerned, we are far from anything that could be called scientific. Many of the studies and meta-analyses of gambling and gambling harms that purport to be scientific are severely lacking. Data is cherry-picked to prove a forgone conclusion. The media laps it up and policy makers use these flawed studies to inform policy.

The anti-gambling lobby and the public-health industry have gambling in their sights. They want to do to gambling what they did to tobacco, despite the harms being considerably less.

This is not just a problem in Great Britain, but is prevalent in most countries in Europe and is now being seen in the United States.

The industry needs to wake up and understand what is happening. If we continue down this path, the regulated industry will have increasingly onerous regulations imposed. They will not stop, revenues will inevitably decline as customers are put off, and the black market will flourish. It will be the 1920s all over again, but with gambling instead of alcohol.

What can be done? I think there are a few things. We need to find a voice. The industry needs to get on the front foot, debunk spurious research, and have a spokesperson comfortable being interviewed by the media and willing to call it out. Be honest with the public and policymakers about the harms caused by gambling. Support the findings of good research, even if it may be detrimental to the industry. Commission research that shows the impact of regulations on our industry.

Perhaps, with a multinational effort, we can push back the tide.